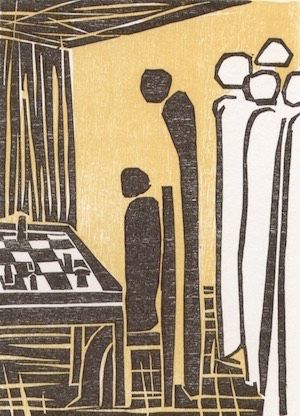

The Royal Game by Stefan Zweig Or Chess Story

“Isn’t it confoundedly easy to think you’re a great man if you aren’t burdened with the slightest idea that Rembrandt, Beethoven, Dante or Napoleon ever lived?”

I have recently finished reading ‘The Royal Game’ by Stefan Zweig (also published under the name ‘Chess Story’), and greatly enjoyed it. I’ll make no secret how I discovered the author.

I had never heard of Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig, in spite of his popularity (including in the United States) during the 20s and 30s, until I had watched the recent Wes Anderson film ‘The Grand Budapest.’ It took me three viewings to decide conclusively if I liked the film (I did), but I was puzzled by some elements of it. Most specifically, the significance of the multiple levels of frame story. The story of the ‘Grand Budapest’ is the story of an art theft as told by an aging hotel proprietor to a novelist, who converts the story to a novel, which is itself being read by a young aspiring writer at a memorial to that novelist. I wasn’t sure what to make of this multiple layering of frame story, until I read that this was a common device in Stefan Zweig’s novels. This and a few other stylistic decision from the movie made a bit more sense with a little knowledge of Stefan Zweig to grant context.

I was interested, so after looking at Half Price for Stefan Zweig novels (and finding none) and looking at the Fort Worth Central Library (and finding none), I flipped through Amazon’s Kindle store and picked the one that sounded the most interesting of his most popular works. I chose this one, and could not put it down after I started, finishing it in an afternoon (at a hundred pages, this is not any great accomplishment, but is still a testament of my interest.)

I take it back. I did briefly set the iPad down so that I could I rush into the bedroom to enthuse about the novel to Amber. After five minutes of excited and (I suspect) slightly incoherent stammering about how good it was, I was back in my book.

The novel tells (via an observer) the stories of two chess masters who meet by accident on cruise ship and play a not-so-friendly game together. One, the world champion, is rude, crude and brutish. A talent for chess is his only redeeming, valuable quality. He is otherwise devoid of all talents, including basic civility. He comes from a family of peasants, and having gotten the hard life early on, you see, he doesn’t suppress the desire to show his scorn for the upper-class gentlemen that tend to make up his competition and observers.

The other is an Austrian lawyer with monarchist sympathies who underwent half a year of interrogation after the Nazi occupation of his homeland. During this time, he is cut-off from all contact with the outside world and anything that could distract him from his current plight. He is denied everything beyond the bare minimum required to survive while he is interrogated for information, night-after-night for months by the Gestapo. He keeps his sanity, for awhile at least, by playing chess games in his head against himself, and so, bit by bit, hones himself into a master player.

The novel is about both the chess game played between the two, which turns out to be evenly-matched, and the story of their lives, and specifically how they came to be not just chess players, but chess monomaniacs. The observing narrator, a man with a casual interest in chess, must simultaneously respect the fact that they play a completely different, higher game than he does, but observes that it comes with a flaw that they can only obtain that level through total obsession with something that a sane person would treat as an idle past time. ( Side-note: A Chesteronian sentiment like this is not a bad way to my affections. ) This sentiment also matches with what a few (former) competitive chess players have told me about competitive play: that eventually you have to choose having a life and a casual appreciation for chess, and being a competitive player and pretty much nothing else, and that this turning point represents where they left off the game. I imagine its true of any game or sport that has formed a league of professional play.

This was a good book, and I’m excited to read more by Stefan Zweig.

blog comments powered by Disqus