Who is Citizen Kane? Best, movie, ever

I watched Citizen Kane for the first time almost ten years ago. I had been pegged with teaching an “English through Film” class at Shengda College in Zhengzhou, Henan, China, and that class required that I build an English class around screening around a dozen classic films. At the moment, I can only remember two of those: Citizen Kane and Casablanca. I have since seen Citizen Kane around twenty or thirty times, and with each viewing, it ascends a little higher in my esteem. And the first viewing had it pegged pretty highly in general. For half a century, it has been seen as one of the best films ever created, and I can’t quibble with that distinction.

The question, though, is what is so great about it? Why is it better than everything else that was made before and since? Lots of people, and I sympathize with them, I really do, are suspicious of this old movie from the forties that film critics say is better than anything that has come since, but otherwise isn’t all that well known. We suspect we are going to be subjected to some avant-garde nonsense that only makes sense if you watch it with a film criticism code-book ready at hand.

We imagine something like this: “Ah, I see. The black suit represents his death, but he has a rose in the breast pocket. This represents his heart, clinging to life. Only having seen this can I understand the film.” Or something similarly pretentious.

The synopsis doesn’t help the matter much. From IMDB : “Following the death of a publishing tycoon, news reporters scramble to discover the meaning of his final utterance.”

I’m no film critic, but I’m going to take a wild-stab in the dark at what makes the film so great, and in doing so, cheat and shoe-horn Gene Wolfe into this. Gene Wolfe once defined classic literature as a book “which can be read … and reread with increased pleasure.” This little quote perfectly encapsulates Citizen Kane’s greatness.

The movie Citizen Kane makes perfect sense on first viewing. It is a rags-to-riches story of how Charles Foster Kane gained his fortune and how his wealth rotted-away his life bit-by-bit until he dies alone and (spoiler) pining for his innocent but impoverished childhood.

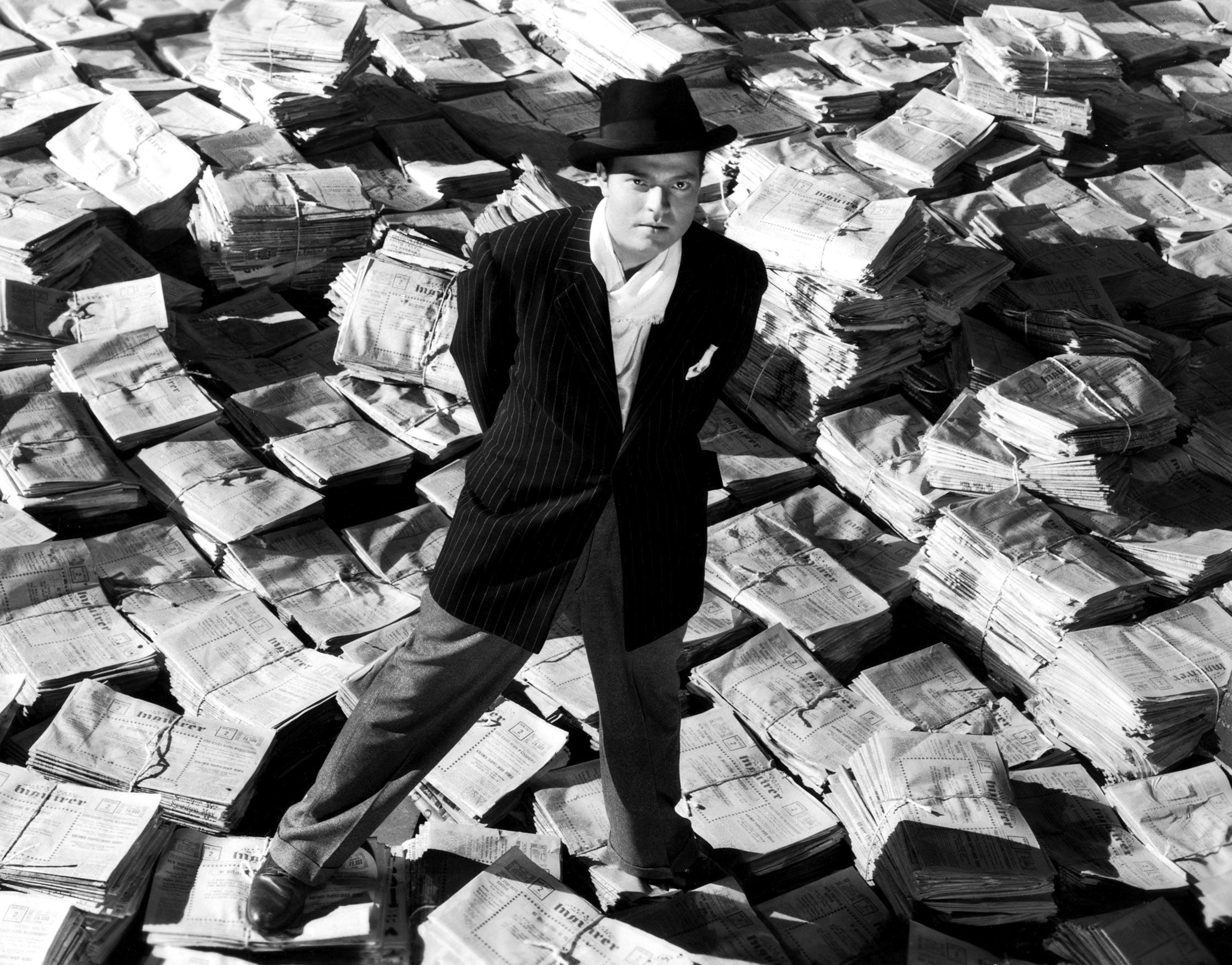

That’s all well and good and enjoyable. That entire arc is consistent, and Orson Welles plays the young Kane as debonair and completely likeable. Most likely it is all you will see on viewing one. It’s certainly all I saw on viewing one, and on that alone, it is an excellent movie. We know this character and we are interested in how his life unfolds, the ups and the downs. Hold on that bit about us “knowing this character.” I’m going to come back to it.

On viewings two and three, you notice more detail. You probably come to appreciate that Citizen Kane doesn’t look like other old movies. There is a reason for this: Orson Welles in his first movie out of that gate, pioneered at least a half dozen filming, editing, and sound techniques that have become standard in Hollywood films to this day. You may also have done some homework in the meantime and discovered that Charles Foster Kane’s life is modelled (and not very discretely) on the life of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hurst, including the failed political campaign and the affair with an actress. You think you have a handle on this Citizen Kane thing.

But nothing in all this makes it the best film ever made, just a really good movie. We’ve had lots of rags-to-riches movies based on real people, both as favorable and unfavorable portrayals. And the whole “The American Dream might not be all its made out to be” angle has, at least in the meantime, gradually lost its edge. At this point, its a great movie, hugely enjoyable, very innovative for its time, but the whole “best film ever made” thing seems to be hyperbole.

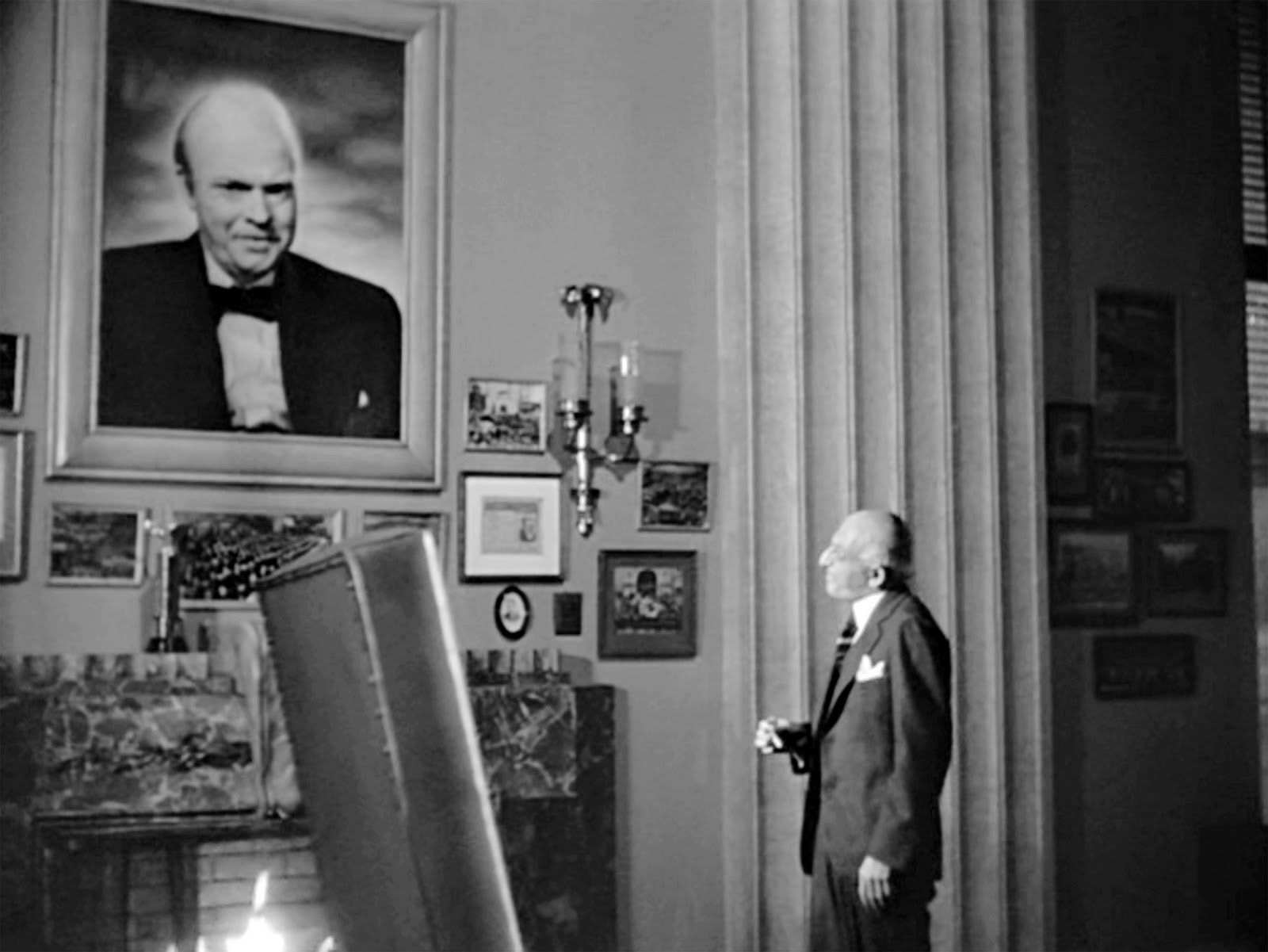

A few more viewings in, and things start to unravel. Remember how we “knew” Charles Foster Kane at the end of viewing one? Now, we aren’t so sure. We realize that we get Kane’s life always from other people’s points of view, and the events always seem to suit their take on things. We realize that if we are to really have an opinion on Kane, we have to have opinions on the individuals telling us about him.

That opens the floodgates, and we see things we didn’t see before, things that were not essential to understand the picture on viewing one, but add depth upon multiple viewings, and none of them require some lit-crit codebook to decipher. Kane’s foster father, the wealthy industrialist Thatcher, sees Kane as a dangerous radical and a communist, and in his telling, that’s all we hear about it. But no one else, including Kane’s blue-blood first wife, sees Kane as either radical or communist. Bernstein gives us all our images of Kane as loveable debonair rascal, but it’s obvious Bernstein has serious case of hero worship going on as well. Leland gives us a harsher view of Kane, as a self-absorbed egomaniac who believes he can buy everyone else’s love and friendship. But, how to put this politely, under the genteel Southern gentleman routine, Leland is a bum, and probably the only person in Kane’s circle of friends who simultaneously was a radical and who was completely depending on Kane for hand-outs. In fact, his job of “dramatic critic” is given to him as a gift by Kane, unlike Bernstein’s role as accountant and business manager. Even in his late life, Leland spends half the conversation with the reporter trying to bum cigars off of him. And, unlike everyone else, who got on with their lives, Leland is cared for by nurses in a retirement home despite having, according to the doctors “nothing really the matter with him.” Susan Alexander, Kane’s second wife…she is trickier.

Susan Alexander gives us, at least on the surface, our worst portrayal of Kane, as overbearing tyrant and bully. But, she tells her story while completely drunk, and there are still cracks in it. Susan Alexander expresses interest in being a singer. Kane spends millions launching her failed singing career. She gives one concert (to bad reviews), and immediately wants to quit. Susan says she would like to live in a palace. Kane builds her Xanadu at a cost that no one even knows how to estimate. Before it is even finished, Susan whines that she is bored of “this dump” and wants to go back to living in New York.

And we are also left with this: Susan’s portrayal of Kane, more-so even than Thatcher and Leland’s, is unremittingly negative. But, Susan in the only one genuinely distraught at his death, and even defends him for a moment.

After a certain point, with each viewing, we feel like we know less and less about Charles Foster Kane, but more and more about Bernstein, Thatcher, Leland, and Susan Alexander.

Let’s return to the opening question: Why is this the best movie ever made? There are lots of movies with tricky, unreliable narration. I think it comes back to the full arc. With most “tricky” movies, the first viewing is simply one of confusion, and as the viewers we have to weigh whether the writer/director is just jerking us around or if there is something to be seen in a second viewing. We are also, very often, left with the impression that that trickiness is a deliberate device of obfuscation: that there really was a straight-forward plot but it has been hidden from us by writing and directing tricks, and we are expecting to jump through hoops to get through those tricks. Now, I will be the first to say that, done well, I really enjoy that process. I don’t mind having a few hoops to jump through.

And Citizen Kane shares with those movies that there is alot lurking under the surface. But that is where the similarities end. Remember, Citizen Kane makes perfect sense on viewing one. Poor boy becomes rich, builds newspaper empire, is rotted from the inside out by his success. No problemo. With each viewing, we see more, but it never becomes really inconsistent with what we saw in viewing one. It’s like an onion, and every layer we peel is sitting organically on top of another layer.

blog comments powered by Disqus